Insider Questions

by Raquel Pinheiro

I don’t remember when I first heard about or listened to Suede. It was long ago, most likely through the British music weeklies.

In September 2024, I joined The Mild Ones, an online Suede fan group. A bit weary at first. However, the Mild Ones are different from most fan groups. Jose (Duarte) and Sara (Bona) the group administrators won my heart, so did the Mild Ones community.

Being part of the Mild Ones left me curious how it is to manage an online open fan community that large for a band that draws such strong emotions as Suede do. The Mild Ones are a place for fun, our life stories, our band crushes, endless creativity from painting to poems, through bracelets and knitting. And music, of course. It’s an equalitarian place. Well known musicians, producers, etc. side by side with fans. It’s a place of debate.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I present you The Mild Ones, and my conversation with Jose and Sara.

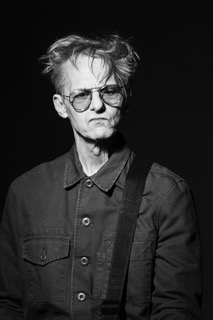

P.S. Dear Sara, we were not all in love with Brett. Some of us took a fancy to the one behind the drums! 😎

Suede are currently touring the UK. They will tour mainland Europe in March, and Asia in April and May. Suede premiered a new song, Tribe, Saturday January 30th at Guildhall, Portsmouth, England. And I really like it. 🙂 It’s the kind of song that makes you want to pick up a rock instrument and start a band.

How did The Mild Ones begin, was it a spontaneous act of devotion, or something that gathered momentum over time?

Sara Bona (SB): We were honestly quite determined to make this project happen. We had been discussing the idea for a few months, and we were really excited about creating a community for Suede fans which, thanks to the existence of social media, could reach as many enthusiastic fans as possible. When we finally felt the timing was right, we set the wheels in motion. It wasn’t exactly a walk in the park, though. Was it, Jose?

Jose Duarte (JD): Absolutely! We both felt it was necessary to have a space where every fan mattered, regardless of their place of origin, whether they’d been fans forever or just discovered the band, whether they’d seen Suede live a gazillion times or never at all, whether they collected every record or didn’t own a single one. Even casual fans, or those who only like a song or two, are totally welcome. Every opinion counts in our group. But it wasn’t easy to bring so many people together, certainly not.

When you first created the group, what was your vision for it, and how close has the reality come to what you imagined?

JD & SB: We just wanted for Suede fans all around the world to have a public space where they could share their love for the band and find out whether other Suede fans were into the same things we are – other bands, books, films, etc. We didn’t have a long-term plan; it was all pretty improvised, but we had the feeling that there were people out there just like us. And, indeed, there really are!

What does the name The Mild Ones mean to you now, given that most of the fans and the band are older? Does it capture a sense of calm, reflection, or continuity?

SB: Choosing The Mild Ones as the name for the group was a bit tongue-in-cheek, really. We’ve been wild, we still can be wild but, at our age, we just want a little peace in our lives, we just want to be mild, while still loving Suede wildly. We can’t speak for other fans or the band, but that’s how we feel.

JD: In our everyday life, we’re quite mild, we like to go unnoticed but trust me, we can be wild at gigs.

And what does The Wild Ones – the song – still mean to you today, both personally and in relation to the community?

SB: I remember watching the video for The Wild Ones on MTV in the 90s, over and over again, after I discovered the band. Back then, I was head over heels in love with Brett (as we all were!), and I was just a 14- or 15-year-old girl, not very good at English yet. Of course, I loved the song but I think I can appreciate the beauty of the music and the lyrics so much more now than I probably did back then. 🙂

JD: The Wild Ones, for me, is the best song Suede have ever composed. Of course, The Asphalt World is the quintessential Suede song but there’s something about The Wild Ones that makes it universal. It reflects an optimism mixed with nostalgia, which makes it very appealing both to us and to most Suede fans.

SB & JD: We both feel incredibly honoured that Brett and the band have, in a way, linked our group to that sublime hymn.

Suede isn’t just the thread that binds this community, it seems to live within it. What does Suede mean to you personally, beyond the music? How has their work shaped the way you see or hold this space?

SB: Suede have ALWAYS been with me, my whole life since my early teens. They were there when I first fell in love, when I first got my heart broken, when I studied my degree in Translation and Interpreting, which I chose because of my love for the English language and the British culture, when I’ve lost loved ones… They’ve been there in my happiest moments and in my lowest ones. Every single moment of my life is tied to a Suede song. They are my band. And, of course, their music has definitely shaped the person I am today.

JD: In terms of music, Suede were my first love. Since the moment I discovered them at 14, they have always been with me. When I felt sad, I found shelter in Suede’s music. I feel their music is like a friend, one that makes me feel I belong.

SB & JD: The Mild Ones is mostly about Suede music, but also about the influence that they’ve had on our taste in other forms of art.

Even your dog carries the band’s name – Suede – which feels both tender and symbolic. What does that say about the place the band holds in your daily life?

SB: Well, when I got my dog, Jose said it wasn’t a great name for her. But it wasn’t his decision, really, haha. I think the name suits her perfectly. She’s moody, she’s an outsider, she barks a lot and howls, and her fur feels exactly like suede. Of course, she’s an Andalusian hound, so her name sounds a little different in Spanish. Now I find myself calling ‘Suede’ out loud a million times a day so, she’s an ever-present reminder of my beloved band. 😀

JD: Okay, I was wrong and you were right, haha. The name really does suit her.

The group remains open, where many communities choose to be private. What guided that choice, was it about accessibility, trust, or something deeper about how you see connection?

SB: Now my question would be, why do those communities choose to be private? It’s all about the music, nothing to hide there. And yes, it’s certainly easier for people to find the group this way.

JD: Sharing content with other groups, at least on Facebook, wouldn’t be possible if the group were private. In the beginning, it was a great way to promote the group around. I agree with Sara: what is there to hide? What’s wrong with your family and friends knowing that you love Suede?

SB: My family and friends are sick and tired of hearing me babble about Suede, hahaha!

Managing a community of over thirteenth thousand members must carry moments of both joy and overwhelm. What have you learned about human nature through holding this space?

SB: In the meantime, we’ve gained fifteen hundred more members! 😀 I’m genuinely impressed with Suede fans but, then again, I totally expected they’d be top blokes and gals! The good moments far outweigh the not-so-good ones.

JD: I’ve learnt that, at the end of the day, and deep down, we’re all very similar, which is a good thing. I’ve also learnt that people enjoy being part of something bigger than themselves. They like to participate, give opinions, share their thoughts with like-minded people, and they need to relax after a long day at work. That’s what social media is for, isn’t it? No drama, just fun!

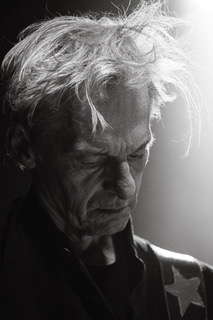

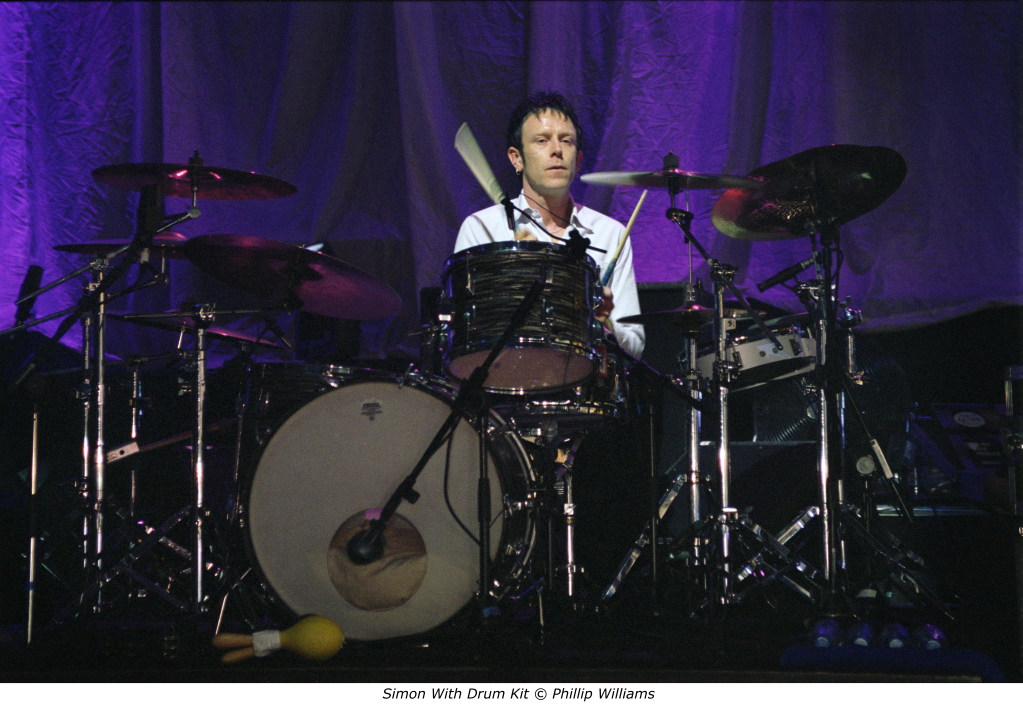

Some members of the band – like Simon Gilbert (Suede’s drummer) – and people who work closely with them are part of the group. Has having Suede themselves within the community affected the way members express themselves, or does it remain a space where everyone feels free to share their opinions?

JD: Not at all! Honestly, it has zero influence. We even wonder if people realise that Simon is a member! We’re also thrilled to have among our fellow Mild Ones other people who work closely with the band, like Paul Khera, Jip Nipius, Mike Christie, Saul Galpern, Justin Welch, Simon Price, Jim Hanner, and plenty of other musicians who are friends with the band: Rialto’s Julian Taylor and Louis Elliot, Emma Anderson, Mark Fernyhough, and Ian Watson, among others. and, of course, the lovely Mariana Enríquez [who wrote the book Porque demasiado no es suficiente: Mi historia de amor con Suede].

SB: And I’m pretty sure Brett must be lurking somewhere too, haha! People here aren’t shy about speaking their minds, even if it’s not always flattering. And that’s perfect: critical thinking and constructive criticism, when said with respect, only makes the space better. Luckily, our members know how to disagree gracefully and still have fun.

Online spaces can often feel fleeting, yet The Mild Ones endured. What keeps it alive, is it the music, the shared nostalgia, or something ineffable that Suede evokes?

SB: In my opinion, Suede isn’t a band for the masses. Their music isn’t easy listening, and the lyrics are not straightforward. I think it speaks directly to certain people, those of us who sometimes feel out of place, those who expect music to say something about life and themselves, those who need to feel poetry and grandness in a world that can sometimes feel devoid of it. It’s music that touches your soul and never lets go. That’s probably why Suede fans are so faithful. It’s not just music; it’s a lifestyle. And once people feel that, they want to stay.

JD: The relaxed atmosphere of the group greatly contributes to its permanence. People know they can talk about whatever they want, whenever they want, without others taking offense and, unfortunately, that’s not true for every group on social media, as the algorithm often favours conflict and bad vibes.

Have you witnessed friendships, collaborations, or even transformations emerge from within the group? Things that remind you why you continue?

JD & SB: We have, indeed! Many a friendship has been forged within the confines of the Mildlands, about which we are truly happy, as it is a way for fans to connect in a disconnected world, to quote Brett.

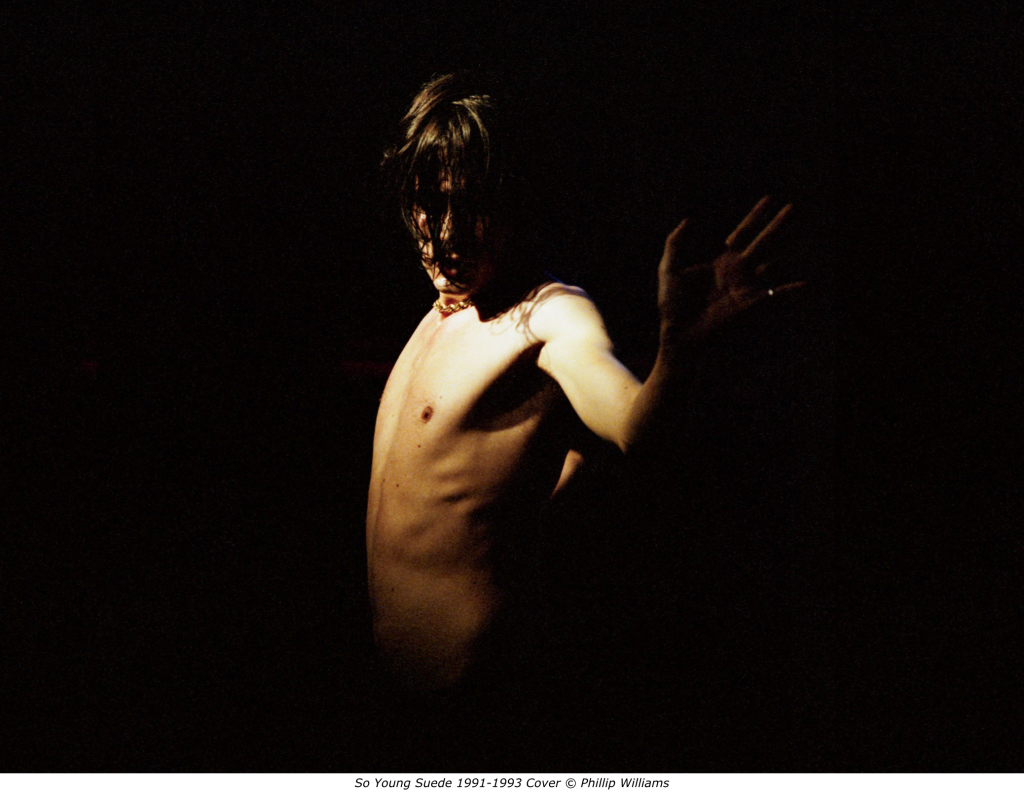

Some collaborations have also emerged, notably the project Swayed with Wayne Readshaw, Jo T. Jones and Carlos Rodrigues, who have made a magnificent cover of So Young.

In their own words: “Remote cover of the classic Suede hit ‘So Young’ featuring Jo Taylor-Jones (vocals, bass and keys), Wayne Readshaw (guitars) and Carlos Rodrigues (drums). Via ‘The Mild Ones’ Facebook group, the trio got together online to record this track at each of their homes before it was compiled across 5,365 miles.” But they aren’t the only ones. We’d also like to mention the best tribute band in the world, our Indonesian friends Animal Lazy, as well as other consummate artists who share their striking covers with the group such as Helen Wong, Lunachangue Tak, Maximilien Poullein, Bettina Korn, and Popping Shi, to name a few.

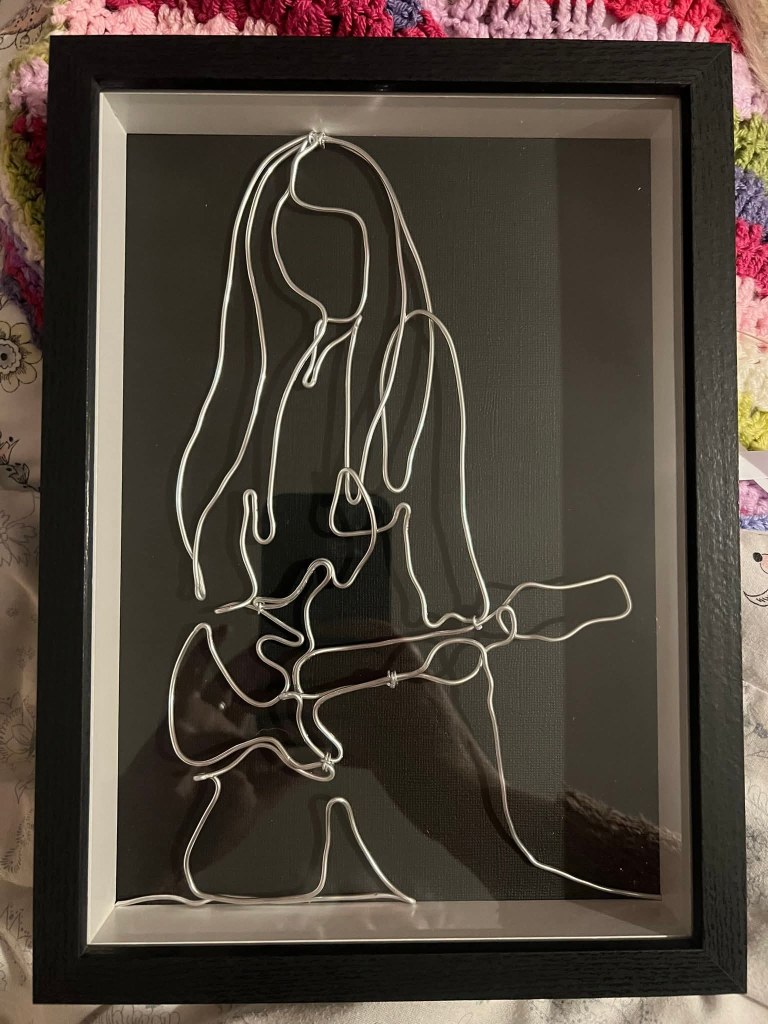

Other talented members have also shared drawings, designs, artistic performances, make-up and jewellery creations with the group including Susan Gallagher, Wanzhou Ji, Carmen B. Leung, Erika Seya, Haruko Masuyama, Laura RK, Ingrid Petry, Lindsey Barton, Mel Langton Art, SW Portraits, Matthew Williams, Hardeep Sihota, Maeve, Isabella Arp, Silvio Balija, Jim Morey, Anna Walsh, Pat Taylor (Patsy), Neil Reid, Simona Valenti, Kay Kitto, Petrol Blue, our two moderators DeanJean Phng and Melissa Waterfield. Even we have shared some poems and drawings ourselves.

We are happy to say that ours is a lovely community full of artistic talent!

Suede’s work often balances elegance with rawness, beauty with disquiet. Do you sense that same duality in the way the community expresses itself?

JD: Yes, we do notice that duality. You can come across posts that are particularly harsh about a song or their latest work, but you can also find posts praising their music with beautiful words. But all opinions are more than welcome.

SB: One of the things I believe people appreciate most about the group is that they feel free to express themselves in whatever way feels right at the moment. Of course, there are limits: we only ask that people remain respectful towards others and the band, but within those limits, everyone is free to say whatever they want, however they want. And yes, that duality is definitely there.

How do you personally stay inspired as administrators, what restores your energy when things get heavy or chaotic?

JD: When things get tough, I listen to other bands like Radiohead, The Divine Comedy, Manics or Pulp to disconnect a bit from everything related to the group. Then, I go back to listening to Suede to restore my energy.

SB: I must confess that I’m not a big fan of social media, so the time I spend on my phone is usually in the group. I’m more of a watcher and reader than a responder, but Jose keeps me informed about everything. That said, I only listen to Suede; I don’t have time for other bands since I have a pretty busy life. And I have Netflix and a lot of books.

After three years, what do The Mild Ones mean to you, not just as a group, but as a living archive of feeling, music, and shared history?

SB & JD: Well, as we’ve mentioned before, this started almost as a joke. We were more like a comedic duo in another space. So the fact that we’ve grown so much, and gone from being just an anecdote to now being the largest Suede fan community, fills us with pride and satisfaction. And it’s all thanks to the fans who, every day, fill our space with stories, anecdotes, photos, information, videos, experiences.

The Mild Ones Facebook | Instagram

Suede related interviews on Mondo Bizarre Magazine:

In Conversation With Simon Gilbert

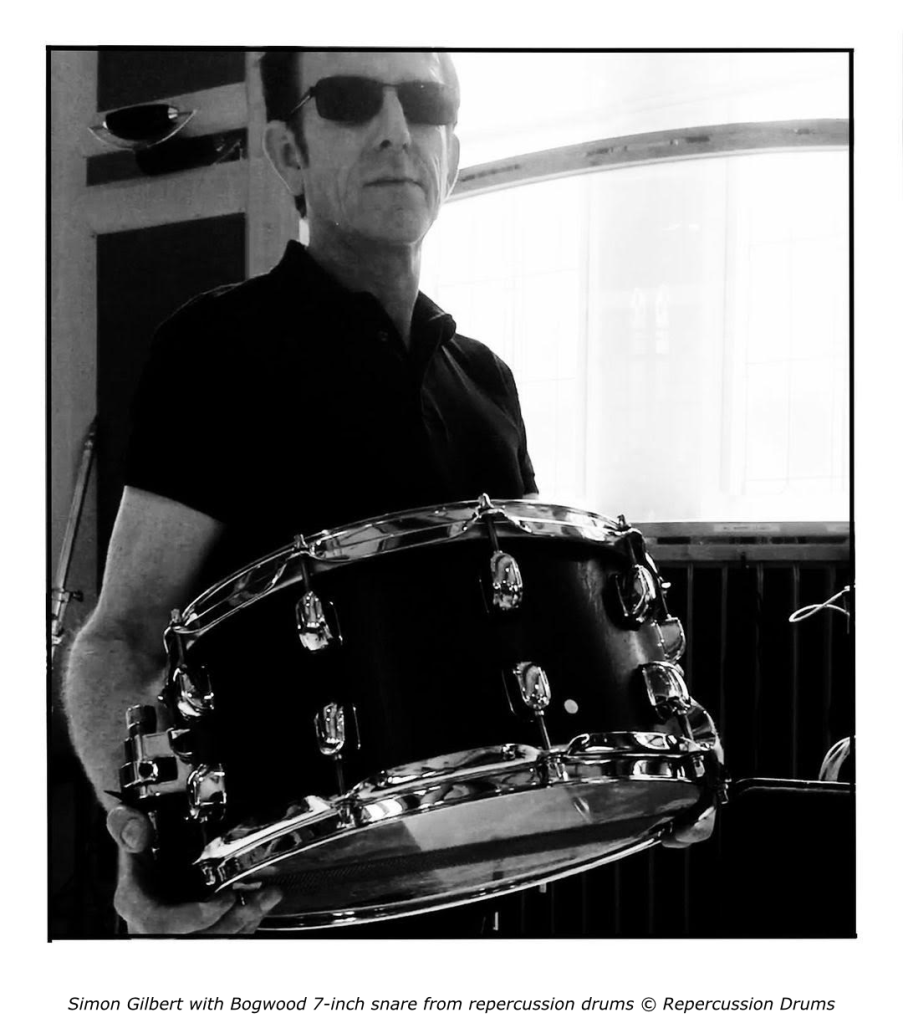

Five Questions With Andrew Johnston of Repercussion Drums

The Asphalt World: Growing Up on Tarmac and Songs – An Essay by Neal Reid